We the people…

From the Publisher:

Hello, thanks for picking up this zine. If you read the first issue in this series, welcome back; you know our schtick. If this is your first encounter with our project, welcome: we’re a small zine publishing press trying our damnedest to do as the cover says: demystify city government. This is the second in a series of three zines with that intent.

We were pretty stoked to see the first zine cycle out as quickly as it did; we’re hoping it’s a solid indicator that there’s untapped civic energy here in La Crosse. Roxanne has long been interested and invested in La Crosse’s city government, but I’m new to this arena. The first zine was easy enough for me to edit because while it was government relative, it was still largely narrative, and story I understand; story is my wheelhouse. But when it came to this second zine—about passing a referendum that starts at the local level but is ultimately aimed not only at the national level of our country’s government, but at its Constitutional core—I was way, way out, struggling in depths I’ve never swam.

The saving grace is, of course, that it’s still a story. A good one, about two people trying to do good in the world. Two people who, when confronted with a gauntlet, chose to run. And they ran—through all the jargon, all the hoops, all the red tape and paperwork and time limits, they ran. It’s not a story about a happy ending, or even a story with an ending, it’s a story where action leads and transformation follows. Not necessarily transformation of surroundings, but of self. Because what do we become when we run at the nation’s heart? Pam and Gary know, they did it. That’s something.

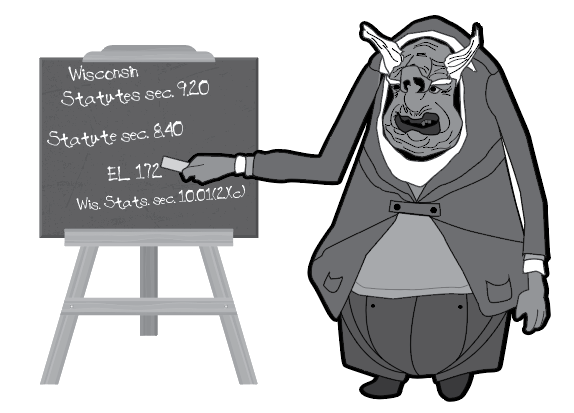

Reading their tale greases the wheels for the city clerk’s section, which is still a jargon-naut (ha ha, word pun), but hopefully it makes more sense once you’ve looked through the lens of two people who agreed to play that game, following the rules as written. Confusingly, confusingly written. And while Roxanne and I take this project seriously, we also think ourselves (maybe too) witty; call it tension alleviation, but we couldn’t help but think of the Vogons from Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. If you know, you know, but if you don’t, Vogons are an alien species who value bureaucracy and systematic procedure above all else, except for poetry, which they suck at, exceedingly, because poetry is not the realm of the bureaucratic, but of the wild ones.

(Regardless, Roxanne drew those Vogons—and the cheesehead badgers—and we think they’re adorable as hell).

So without further ado, please, enjoy this zine. We’ll catch you again for the series finale. Thanks for reading.

Cheers, Roxanne and Rachel

“We The people…” by Pam Knudtson

When we learned to do a petition drive that calls for a referendum, we learned as we went, and while we found and gained a lot of support before, during, and after the project, it would have been impossible to grasp the scope of the work at the outset. This zine doesn’t explain our whole process; it’s a story of what we did, but not a “how-to” guide. For that, we recommend the Wisconsin United to Amend (WIUTA) website.

This next section offers definitions and specific wording, explanations, and steps in the various processes that are key to understanding our story. Unless otherwise indicated, the information is taken directly from the WIUTA City and Village Handbook, which we used as our guide.

What is a Resolution? What is Referendum?

A resolution is a statement that is a proposal for a solution to a problem.

A referendum is a question that is based on a resolution that voters are asked to approve on a ballot. The problem we are trying to solve is big money in politics.

What is the problem and solution we

proposed with our work?

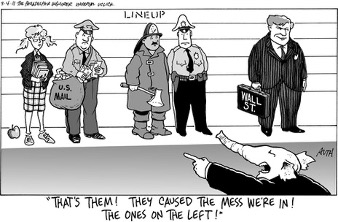

Problem: How can politicians represent us when they’re given

millions to represent someone else?

Solution: To restore our representative democracy, we must amend the Constitution to clarify that money is not the same as free speech and that only real people should have inalienable rights.

What is the exact wording of the Resolution and the Referendum we promoted?

PROPOSED RESOLUTION

By the [CITY/VILLAGE] of [MUNICIPALITY] Electors

Supporting a Constitutional Amendment

Whereas, government of, by, and for the people has long been a

cherished American value, and;

Whereas, free and fair elections are essential to democracy and

effective self-governance, and;

Whereas, corporations are not and never have been human beings or persons, and therefore are rightfully subservient to human beings and governments as our legal creations; and rightly are provided ONLY privileges by the states, and;

Whereas, interpretation of the U.S. Constitution by appointed

Supreme Court Justices to include corporations, unions and other organizations in the term “persons” has long denied We the People’s exercise of self-governance by endowing corporations, unions and other organizations with Constitutional protections intended by

the Framers for ONLY We the People, and;

Whereas, in 1976 in the ruling on Buckley v. Valeo. The untenable decision of the Supreme Court changed the course of American elections and established the doctrine that spending money to influence elections is a form of speech; and;

Whereas, on January 10, 2010, in Citizens United v. Federal

Elections Commission, the Supreme Court overturned a century of

precedence—by ruling that corporate spending on elections cannot

be limited under the First Amendment; now therefore,

Resolved, that “We the People” of the [City/Village] of [Municipality], Wisconsin, seek to restore democracy from the expansion of corporate personhood rights and the corrupting influence of unlimited political contributions and spending. We stand with communities across the country to support passage of an amendment to the United States Constitution stating:

1. Only human beings are endowed with constitutional rights — not corporations, unions, nonprofits or other artificial entities, and

2. Money is not speech, and therefore limiting political contributions and spending is not equivalent to limiting speech.

Further Resolved that the [City/Village] of [Municipality] Wisconsin Clerk is directed to forward a copy of this resolution to our state and federal representatives with instructions to enact resolutions and legislation to advance this effort.

APPROVED by the Electors of the [City/Village] of [Municipality], Wisconsin, at the [Date of Election] Election.

By: [NAME] [TITLE]

The following is the compromised referendum ballot language we negotiated with the city clerk. It is the short version of the resolution language (shown on the previous page) that people read before they signed our petition. City clerks have full discretion to write the ballot language as they choose, and the La Crosse City Clerk chose different language, so we negotiated with her for changes to her wording to reflect our Resolution language more closely.

Proposed Ballot Language

Shall the City of La Crosse adopt a resolution in order to limit spending to influence elections so as to allow all Americans to have an equal say in our democracy that supports a U. S. Constitutional amendment stating: (1) Only human beings are endowed with constitutional rights, not corporations, unions, nonprofits or other artificial entities; and (2) Money is not speech and, therefore, regulating political contributions and spending is not equivalent to limiting speech?

Our Story

Back in 2017, we had a general sense of wanting to “do something” about the way things were going politically, both in Wisconsin and the country as a whole, but the initial impetus to take action traces back to the fall of 2016, to the presidential election of Donald Trump. Like many people at that time, we were unprepared for that election.

On that particular day, I (Pam) started work at 6 am as a poll worker at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. Unlike any other polling places in the city, the university location featured large television screens, part of the student activity center hubbub. The screens surrounded the long lines of voters, and as we closed the voting at 8 pm and started preparing ballots for the count, students began to gather around those screens. As the night went on, we were surprised to see crowds of young men cheering at one of the televisions, while at another, students were despairing, shaking their heads in disbelief, supporting each other, or quietly waiting for the numbers that never turned around.

One of the volunteers I worked with that day was the local head of a national NGO that focuses on conservation policy, and they explained that this election was closely tied to Russia; now that the polar ice cap had melted, the competition for Arctic oil drilling rights would be between Russia, the EU, and the US, and it would ignite a lot of conflict. This was news to the rest of us at the table, and the first of many sensational revelations in the years to come.

As I drove home that night, after 2 am, I heard that Wisconsin’s electoral votes had gone to Trump. I arrived home to hear the announcement that Clinton had made the call to concede defeat. Gary was waiting up, in the same stunned state as I was. I collapsed in exhaustion, not only from the 16-hour workday, but also in consideration of our personal pasts and futures after yet another political shock.

I had retired in 2012, a teacher for 34 years, and Gary had retired in 2013 after many years with the US Postal Service. He had long served as the local president of the National Association of Letter Carriers, and I was an active member of the La Crosse Education Association—an organization that greatly improved conditions of teachers’ lives over the course of my career, improvements I appreciated. Our involvement in those institutions had not prepared us for how we would witness the undermining and attacking of their foundations in our final working years.

In 2010, when Governor-elect Scott Walker declared that he would unilaterally decertify all state public employee unions (except for fire and police) as soon as he was sworn into office, we recognized the threat; teachers and other public workers geared up to save their rights in 2011, committing to a full year of protests. Hundreds of thousands gathered at the Wisconsin state capitol, and a massive petition drive to recall Governor Walker began. Gary’s experience working with the public door to door over the years made him an exceptional petitioner in that drive.

As our political understanding grew, we soon recognized the connection between this debacle in Wisconsin and the 2010 Supreme Court decision, Citizens United vs. FEC (Federal Election Commission). The court held 5-4 that campaign finance laws could no longer prohibit independent expenditures for political campaigns by organizations such as corporations, nonprofit groups, labor unions, and other associations. This decision was based on the court’s interpretation of the free speech clause of the First Amendment, which already held that money is a form of speech. Once again, organizations were given the same right to freedom of expression that only individual human beings once held; organizations attaining the right to give political donations to elected officials further upholds the false equivalency that money equals speech.

Once we saw the connection between these two 2010 events, we absorbed all we could from the numerous publications and programs that told this story that few had seen coming: how big money organizations had become the greatest influence in politics, creating chaos within a government many of us had assumed was tasked with determining what was best for the common good and upholding that public good with the law.

When Koch Industries opened an office across from the capitol in Madison in February of 2011, and their Americans for Prosperity offices began to open in cities across the state, it was clear that powerful individuals and corporations were beginning to exercise their new-found rights to ply politicians with huge financial power and rewards. We saw that Wisconsin would be a testing ground for how the free flow of big money could change the political environment and in turn, the quality of life, all in a state that had, once upon a time, been one of the most progressive in the country.

These events inspired many people to get involved in organizations such as the League of Women Voters, the Wisconsin Grassroots Network, the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, and Common Cause: all cross-partisan, issue-oriented groups. These groups helped to explain how we had arrived at this point and what could be done to fight against these changes, to fight for democracy. Some might say this was to no avail, as the Walker recall election failed, and everyone watched as a hostile governor and elected representatives worked with the state’s and nation’s most powerful business interests to defund, dismantle, and privatize Wisconsin’s government, schools, and services. Senior public workers left their professions in droves, walking away before the delayed income and benefits they’d worked for over their careers were stolen from them before they retired. Those who were not able to retire struggled to meet the new challenges brought on by massive reductions in funding. The sudden shortages of people willing to enter those professions and work under the new conditions created problems we’re still struggling with today, more than a decade later. Laws were put into place that allow for the ease of privatizing education, taking money directly out of budgets needed for public schools’ operation and transferring it to a voucher program for parochial and private schools, neither of which are held to the same standards of accountability as public schools.

In similar fashion, the United States Postal Service, where Gary worked, began to struggle under the weight of a 2006 law that requires the employee retirement program be fully funded 75 years in advance; full funding for employees who haven’t been born. With the USPS now having to direct 5 billion dollars of its income into retirement funds,

employee unions came under heavy pressure to concede at the bargaining table because of the budget shortfalls caused by this requirement. Private corporations, with their millions of dollars, had been lobbying Congress to promote this law for a long time, crippling the constitutionally mandated United States Postal Service and providing more opportunities for themselves.

Soon, as the private forces that had taken over the state and federal agencies grew in power, Wisconsinites began seeing similar changes happening everywhere. The politics of resentment—brought in by big money groups’ malevolent PR machines—soon took hold, creating a previously-unexperienced division among people, driving just enough disaffected Wisconsin voters to push Donald Trump over the line for an electoral college win in 2016.

Gary and I are informed and independent voters who look at the candidates’ histories and their platforms to decide how we vote, but in Trump’s case, so much news had already been made of the hypocrisy and corruption involved in his approach to power and the presidency. If he was elected, we could only see the conditions of our lives and the overall state of Wisconsin continue their downward slide.

Many respond to the election

A few days after the 2016 election, the La Crosse Area League of Women Voters hosted a public forum, inviting Matt Rothschild of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign to help attendees understand the election and offer suggestions for what to do with such feelings of bewilderment. This was one of several meetings that like-minded people attended to figure out what they could do next. Matt discussed how the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision could be considered an underlier to all the events leading away from the common good, toward oligarchy. Gary and I noted his recommendation to contact George Penn, leader of Wisconsin United to Amend, the

organization running the statewide campaign to use grassroots work to get big money out of politics.

Another local group that formed in La Crosse after the election was New Directions, led by Roz Schnick. The group drew hundreds of local people looking to do something about the impending Trump administration. Roz accumulated a list of over 200 people who expressed an interest in grassroots action. It was helpful for everyone to recognize that many people shared the same frustrations and deep concerns.

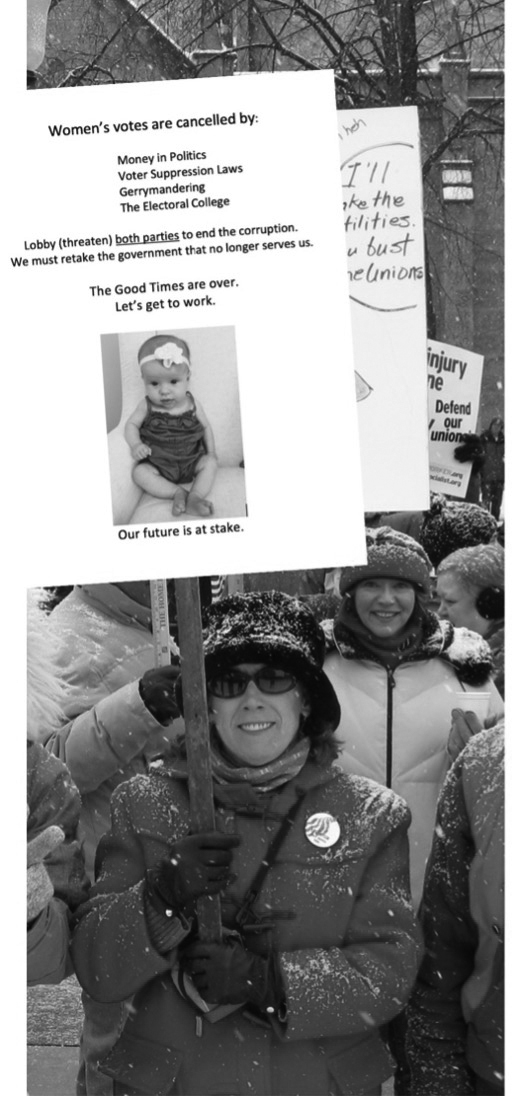

On January 21, 2017, women around the country organized nationwide to march in protest of a Trump administration. We prepared to go to the march in Madison by making a sign; as new grandparents, we had started thinking about the political legacy we would be leaving to future generations, so we decided the sign should address that problem and what we saw as its solution. We laugh now when we compare the didactic tone of our sign to the humor and outrage expressed by others that day, but all the same, it summarized our approach to action for the coming months.

WIUTA, the constitution and the resolution

After attending the Women’s March, we remembered Matt Rothschild’s advice and visited the WIUTA website. WIUTA calls for and promotes nonbinding advisory referendums at the local level to convince our state lawmakers that the majority of citizens of Wisconsin want a state constitutional amendment that declares that money isn’t speech and large wealthy organizations that use money to manipulate government—such as corporations—are not people. Having this language in our constitution would address the problems we find in the Citizens United Decision, and it would nullify the Supreme Court’s rationale for their Citizens United decision.

The WIUTA website lists the 169 municipalities in the state that have already approved WIUTA’s resolution, usually supported by over 80% of the voters when the resolution is brought to referendum. As more and more resolutions are approved and passed in communities across the state, the group believes it will become impossible for elected officials to ignore the Wisconsin people’s demand: to reverse the damage done by the Citizens United decision with a state constitutional amendment.

Once state legislators are convinced to act by the growing number of municipalities in favor of WIUTA resolutions, they will be asked to pass WIUTA’s amendment to Wisconsin’s constitution. This would make it clear that the rights protected in the U.S. Constitution are those of individual human beings only, and that the spending of money is not speech and political spending should be limited, allowing all Americans to participate in the democratic process.

Twenty-two other states have already made this change to their constitutions, and WIUTA’s goal is to have Wisconsin be the next state to do so. They believe that the U.S. Congress is unlikely to initiate the process of passing an amendment that takes power away from their donors, so WIUTA works at the state level to develop the necessary pressure to force Congress to eventually act. The goal is to have so many states with this amendment to their constitutions already in place that each state’s Congressional representatives will take heed and propose the amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

To be clear, there are other means of reversing the Citizen’s United decision. A future Supreme Court composed of different judges might overturn the decision, but then another, further future Supreme Court could overrule that decision, so that isn’t a real solution. Congress could enact laws that negate the Citizens United decision, but these laws would always be subject to the Supreme Court finding them unconstitutional. Only by amending the Constitution can we end the corruption of our democracy at the hands of large and often secret monied interests.

Achieving this goal promises to be a long, difficult process because our country’s founders wrote our Constitution to be complicated to amend—complicated but not impossible. Twenty-seven amendments have already been made to the U.S. Constitution. With 38 states needed to ratify any constitutional amendment Congress would propose, those 22 states that have already passed this “We the People Amendment” represent the momentum for success needed to attain the additional number for ratification. WIUTA is not the only group with a goal to amend the constitution, but Gary and I agree that it is the best group insomuch that it works at the grassroots level, and we believe that kind of activism is the best way to achieve the goal.

The best feature of the Wisconsin United to Amend website is the incredibly specific directions and tools the organization provides for carrying out the passage of a local resolution against money in politics. All the advice, forms, and materials they provide are accurate and

necessary. After carefully examining the website’s information, we decided to take the next step.

Beginning the work

Early in 2017, we contacted George Penn of WIUTA. He immediately asked if we had a group of people ready to work with us, explaining that there are several ways to get a resolution on a ballot, and they all require groups of people. In municipalities where the population is small, such as towns and townships, or in the case of counties, where the population is spread out, it’s common practice to go directly to the town or the county board, make the case for the referendum, and then ask them to vote to include it on the next election’s ballot. But for a city like La Crosse, the ideal practice is to go straight to the citizens with a petition for them to sign, telling the city council to include the resolution on a ballot. This gets both the city government and the voters ready for the referendum, because petitioning requires a conversation, an opportunity to discuss the issue in a variety of ways during the process. If the petitioners get the required number of signatures, they simply inform the city council that they’ve done so, and that they want the city council to put it on the ballot, rather than council passing the resolution with a vote among themselves, which is their other option.

George reminded us of the wealth of resources the WIUTA website provides for conducting a petition and asked us to familiarize ourselves with that information. He also pointed us to the section that outlined the most important petitioning requirements we would find: the strict time limits.

There are limits on the amount of time required between the petitioning process and the actual election, and on the amount of time petitioners have to collect the necessary number of signatures. The signature requirement is 15% of the number of people who voted in the last governor’s election, so for La Crosse that meant 2,958 signatures. George told us that if we wanted to do this within the coming year, it would be important to look at the election schedule for the spring of 2018. Petitioners have 60 days to collect signatures, so there were certain criteria to consider in

choosing the time frame for those 60 days: begin at least 6 months before the target election, choose months when petitioners will be comfortable outside, look for a time of year when there are numerous public events happening in public spaces. He warned that if we didn’t have enough people working with us the task would be very difficult. He said that the WIUTA website had every tool we would need, but we had to find the people to use them and choose the best timeline.

Our first thought was to approach the organizations we already belonged to for recruiting petitioners and other helpers; this led to our first lesson in grassroots organizing: you must know what you are talking about to convince others to join you. In our case, we needed to build confidence in presenting the rational and legal intricacies of passing a constitutional amendment, both in our state and in Congress. We learned to summarize our goal and the reasons for the goal in the short time we were given. We studied the information so we could answer questions correctly and clarify any misconceptions about what we planned to do.

To find our volunteers, we found it best to go directly to the people in organized groups while they were meeting. We honed a 10-minute explanation about what we planned to do and why. Preparing for these talks was the best way to familiarize ourselves with the details.

We presented our request for help many times. Some of the established organizations we thought could help us already had position papers about why they could or could not endorse our initiative. So even though an organization might be dead set against an issue—such as big money in politics—they might already have their own plan of action for fixing it. Or they might oppose our plan based on conflicting ideas. We found that we had to know everything about our campaign: while talking to some politically astute people, they took advantage of the discussion to explain why our plan wouldn’t work or why it could even be dangerous. We carried on, learning more every day. Once we convinced our audiences that we understood the problem and that our plan was solid, we accumulated a long list of people interested enough to sign up for more information.

We spent months meeting with every group we could find. Because of the political climate in 2017, those groups were almost all progressives, looking for ways to change things. WIUTA is a cross-political, nonpartisan organization; voters with both Republican and Democratic leanings are against big money in politics, in equally high percentages. We noticed that whenever we spoke to local elected officials, there was no difference in attitude between Republican and Democrat in their favor of our work. These are the people most likely to suffer the frustration caused by monied organizations encroaching on their decision- making.

We gradually accumulated a contact list of more than 150 people who were interested in learning more about our petition. Now that we had also armed ourselves with the information we needed, we were eager to begin the education phase, for them and for the voters.

We were also ready to begin our relationship with the office of the city clerk. We wanted to talk to her early in the process so she would understand that we were there to learn from her, that we were serious and informed, and that we knew collaboration with her was essential. We met with her several times to present our timeline, confer on forms and processes, and find out exactly what her knowledge and attitude would be in helping us with our endeavor. One of this project’s greatest rewards was the experience of working with excellent public servants: the mayor, city council, and everyone in the city clerk’s office. City Clerk Teri Lehrke was fully aware of the intricacies of a petition drive that calls for a referendum. She recalled that several had been attempted during her tenure, but none had met the requirements for success. She was encouraged by our preparation and wished us well.

We began publicizing our plan to hold meetings that would present a more detailed picture of our project to the people on our list and to the media. We sent and resent messages to all the organizations we had met with and to the people who had signed up. We wrote and sent press releases and letters to the editor to further our reach. We also proceeded in making arrangements for no/low-cost locations to hold the meetings we would be hosting over the coming months.

And here we should talk about money. We had no money. To begin with, Gary and I paid for all our own printing, postage, doughnuts, and coffee, as we had expected to do. After a while, people started asking where the money was coming from, and when they saw the progress we were making, they began to pass the hat and send us checks. Of the 150 people on our list, most contributed money, some contributed time, and a precious few offered to petition.

The use of money in our own campaign against big money in politics was a struggle for us. We are so grateful to the generous people who contributed money to our cause, but we still believe that if the people who gave money had petitioned with us instead, talking with their friends and neighbors, we believe the results of our efforts would have been even better. This experience helped us to see more clearly than ever that people talking with other people and working together to make our voices heard by those in power is the only way we will be able to maintain our democracy.

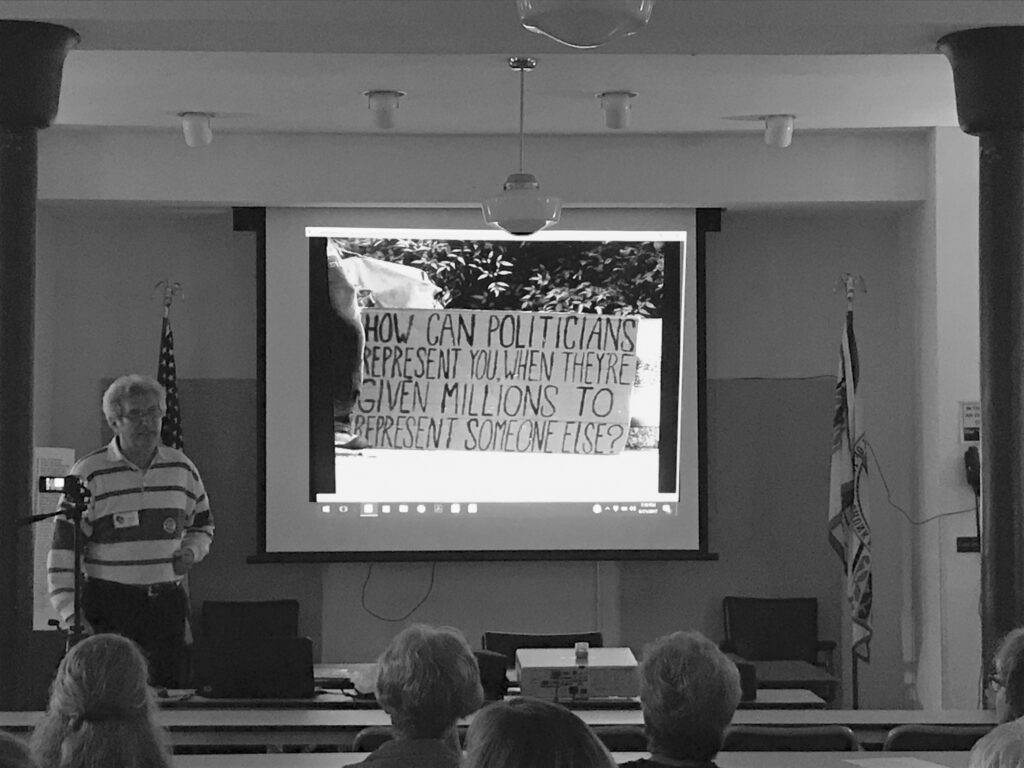

The Petition Drive

George Penn came to town a couple of months before our petition drive to deliver a rousing presentation about the history of corruption that big money has wrought in our country. At that time, we had not received any endorsements from any of the organizations from which we drew interested members, and there were still some dire warnings and misrepresentations that we continued to chip away at until our final success. If you’ve ever worked on anything that is more complicated than it seems, or the people you expected to understand didn’t, or they refused to learn beyond their own expertise, you know that there are times when you have to proceed without their help, or you risk getting too bogged down to act.

So after George’s presentation and several radio interviews and articles in the local paper, we finally decided to proceed, despite the fact that the original 150 enthusiasts had dropped to about 30 people ready to learn the work of a petition drive (exactly as George had predicted).

We hosted two training sessions on how to petition according to WIUTA’s directions. We copied petition pages, made identification badges, rounded up clipboards, made signs, and created city maps divided into sections for petitioners. Farmers’ markets were prime territory. Public sidewalks in front of businesses with a lot of foot traffic—such as grocery stores—were especially productive.

We petitioned during September and October of 2017. Our workers searched the lists of area events, including outdoor concerts, city festivals, celebrations in the parks. Parades. The front plazas of public buildings such as the library and the post office. We set up a table at any event that would have us.

Our petitioners learned to gauge how far into their elevator speech they would need to go to get the signature. Some people took a quick look at the posters we carried and signed without needing further explanation. Others were suspicious and either ignored us or required a long discussion. For many people, a simple request to sign our petition so we could have a chance to vote on the issue was enough. We explained that they could sign the petition for the referendum even if they would vote against the resolution in the election. Gary found that his ability to approach his old postal patrons with a friendly, quick-and-to-the-point greeting made him a confident petitioner. This skill, along with his experience gathering signatures to recall Governor Walker, made him an inspiring trainer and most prolific petitioner. Of all of the signatures we eventually gathered, over half were brought in by Gary.

We knew we had reached our goal of 3,400 signatures before our deadline, but we continued on until the last day, reminding ourselves that we were gathering signatures to both meet the requirements to hold the referendum and to make as many people as possible aware of the problem. When our time was up and any incorrect signatures were eliminated, we had collected 3,489 signatures.

We were proud to present those signatures to the city clerk, and after she certified them, we were met with enthusiasm and encouragement from the city council when we informed them that we chose to have the referendum be included on the ballot rather than having them simply pass the resolution with a city council vote.

After we took some time to rest and celebrate, we began to consider what else we could do to prepare the voters before the April election. Though we had not done any fundraising, we discovered that many of the individuals not inclined to hit the streets to petition were willing to contribute money to cover the cost of our few expenses.

We began our voter education drive regarding money in politics and developed a get-out-the-vote campaign. On an internet search for national leaders in the money-out-of-politics movement, we discovered that Frances Moore Lappé had recently published a book on the subject, Daring Democracy: Igniting Power, Meaning, and Connection for the America We Want. Lappé is a long-standing and highly respected activist; her 1971 book, Diet for a Small Planet, caused a revolution in the ways we think about food and how it affects our environment. Diet for a Small Planet has been in print since it was published, and her ideas have had significance across generations and around the world.

Upon reading her latest book, we contacted her organization, the Small Planet Institute, to find out if she would come to La Crosse to give a talk about money in politics. We were surprised to find that the coauthor of Daring Democracy, Adam Eichen, was available to speak on the date we needed him. When the Institute realized our low budget operation, they offered to send him for only the cost of transportation from their New York location. We agreed immediately and started looking for a place we could afford to hold the talk. We found some possibilities at local universities and were in the process of pursuing them when we found out that Mr. Eichen was leaving for a new position at Harvard and would have to cancel, but if we wanted Ms. Lappé to come speak instead, under the same terms, she was willing. Of course, we accepted that alternative! Our excitement quickly turned to stress as we considered the arrangements we needed to make within a few weeks. With help from supporters at Viterbo University, we found a theater space at no cost that was large enough to accommodate a well-known speaker. Now that our work had proven successful, organizations we had reached out to earlier pledged their support and endorsement.

Around this same time, we wanted to find a way to remind the people who had signed our petition to now go out and vote on April 3. La Crosse Mail and Print Solutions was willing to give us a good rate on postcard invitations to Ms. Lappé’s speech, so we sent cards to all 3,489 citizens who had signed the petition. The postcards also reminded them of the election date, and that the election would include the referendum. Despite the fact that we had to reschedule the event due to a snowstorm, Lappé’s speech was inspiring and very helpful in convincing the 200 people who attended that the present system for political campaign finance is a major threat to our democracy. We have so many people to whom we’re grateful for pulling off such a great event, in a perfect venue, for so little cost.

Overall, we were also fortunate to receive so much press coverage in La Crosse. By using press releases and letters to the editors to generate interest, our work soon became a focal point of all of the town’s media, from the start of the petition drive all the way through to the election follow-up.

The Election

I found myself working again at the UW-L polling place on April 3, 2018. A spring primary draws fewer voters than a presidential election, so the day wasn’t nearly as long, and the atmosphere was far less charged. The results were registered early that night and revealed that 87.98% of voters approved our resolution.

Final Thoughts

As I ran through the questions I wanted to answer about our project in this zine, I realized there are many answers to the question of why we jumped into this civil action project. When we did what we did to solve the problem of money in politics, we were sure of our goal before we began. As others questioned our motives and what we expected to achieve, we were confident in our answers. But even now, in retrospect, after the success we worked for, we continue to develop new theories for why we did such a thing.

We learned that some people consider it ridiculous to think they can do anything about money in American politics. We sometimes heard “Good luck with that,” when explaining the petition drive. Anyone with a sense of political reality knows that the ways in which politicians are influenced by the money they’re given to further their careers is part of a system deeply entrenched with the organizations that also run our economy, provide us information, and make us feel safe. It is too much to untangle. Quixotic is surely the term for what we did, especially for a retired letter carrier and a teacher.

So now, after all of it, we’ve come to the conclusion that we petitioned the voters because it was one of the few things people like us can do, within the structure of our government, to contend with the loneliness that comes from the lack of power we feel in our times. Ultimately, we hope that the people who have more power than we do to solve this problem will begin to recognize us, that they will start to see themselves and their lack of will to do anything as we see them. We don’t believe change will ever happen if people like us stop working to be seen and heard. We hope that our story will encourage others to act for the changes they want.

In 1995, I heard about a plan for a North-South Transportation Corridor that would rip through our beloved marsh, along with several underrepresented neighborhoods. The only people notified of the Department of Transportation (DOT) meetings were the property owners in the direct path of the planned routes, so even though I lived very close to the corridor, I had no idea it was being talked about. A few of us got together and made flyers, alerting people to the project and the upcoming public meetings. We flyered every house on and close to each of the three proposed routes and we sent letters to the editor of the La Crosse Tribune.

Once the flyers started circulating, the press contacted my friend whose phone number was on the flyer. When they asked what group she was with–it was just three single women who lived in the neighborhood—she made up a name: Livable Neighborhoods. Once people started coming to the public meetings, and outrage for the project grew, we formed an official group using that name. Over the course of several meetings, we discovered that despite it already being funded at the state level, the city hadn’t financially committed yet, and the DOT needed the city to share 20% of the cost; we had to stop the city from committing the funds. However, since every relevant elected official from La Crosse to Washington, DC, including our mayor, was in favor of it, the council would certainly vote to fund the project. We decided a referendum was necessary.

For the referendum, the question had to be phrased in a particular way. It needed to be in a positive form, so we couldn’t say, “We don’t want to fund the road.” It had to be “The city would not fund the road,” and you had to vote yes. We had to do a lot of public education about that because it seems counterintuitive to vote yes when you’re really voting no. Keep in mind this was the 1990s, and there wasn’t any social media; we had to hold a lot of informational events, which we held at Jules’. At one point we even had a huge map—probably six feet tall—that showed what the corridor would look like; we had it up on the wall for about a month so people could see what we were fighting.I was co-chair of the referendum committee, so I and others organized the signature gathering for each district. Once we collected all of the signatures, a very large group of us presented them to the city clerk. At that point, the city council could have just accepted and passed the question, but they chose to put it to referendum. It passed overwhelmingly: about 63% in favor of the referendum.

It was only a two-year binding referendum, but the corridor still can’t be built. The mayor and the council understand the will of the people; 63% is basically a landslide, especially when you consider we were outspent by a group of businesses that formed in support of the road. The decision was reaffirmed in 2020 with a council resolution proposed by Mayor Tim Kabat and approved unanimously.

If anyone is interested in the North-South Transportation Corridor referendum, the public library has all the materials from Livable Neighborhoods in their archives.

A referendum is defined in Wisconsin Statutes as “an election at which an advisory, validating or ratifying question is submitted to the electorate.” In Wisconsin, referendums may be placed on a ballot through a number of means. Most commonly, they are initiated by a governing body or through a citizen petition initiative called direct legislation.

While only 24 states allow citizen ballot initiatives and referendums at the state level, virtually all states allow them at the local level. Wisconsin does not have a state-level initiative process; however, all Wisconsin cities and villages have a process. There is no process for towns, school boards, or county boards.

Wisconsin Statutes sec. 9.20 governs the process for direct legislation, which allows an elector of a city or village to submit ordinances and resolutions (may be referred to as “legislation” hereafter) to the governing body following circulation of a petition and collection of the required number of signatures insisting on the passage of the legislation. If the governing body fails to pass the legislation (by either voting no on the proposed legislation or not considering the legislation within the required time frame), then the question of passage is put to the voters by way of referendum at a spring or general election. If the governing body votes yes to pass the legislation, without alteration, it becomes law without referendum.

A direct legislation referendum is always binding. A resolution or ordinance adopted by direct legislation is not subject to the veto power of the mayor and cannot be repealed or amended by the governing body for two years. However, laws adopted by initiative may be repealed or amended by another initiative action.

When considering a direction legislation initiative, it is recommended to seek legal counsel. The entire process is governed by Wisconsin law and an attorney will assist in ensuring compliance with all statutory requirements. Additionally, you need to be mindful of the timing. Contact the clerk of the city or village to discuss the process, timing, and signature requirement.

The first step is to draft the ordinance or resolution. The legislation must be in final form before circulating. Once complete, the legislation is attached to a Petition for Direct Legislation and is circulated for elector signatures. The preparation and form of a direct legislation petition is spelled out in Wisconsin Statute sec. 8.40. A sample petition (EL-172) can be found on the Wisconsin Elections Commission website https://elections.wi.gov/.

A number of electors equal to at least 15 percent of the votes cast for governor at the last general election in the city or village must sign in support of the petition. In addition to signing, the elector must provide their printed name, residential address, municipality of residence, and the date of their signature.

Once a petition begins circulation, the clock begins. From the date the first signature is obtained, the minimum number of required signatures must be collected and the petition filed with the municipal clerk within 60 days. Once filed, no signature may be removed from the petition.

Who may circulate a petition? Individuals who are either a qualified elector (a U.S. citizen, 18 years of age or order and not otherwise disqualified from voting) of Wisconsin or would meet the standards of a qualified elector if they were a resident of the state.

Who may sign a petition? Qualified electors of the municipality (city or village) for which is the legislation is written.

Circulators must personally circulate the petition and witness the elector signing the petition; petitions cannot just be left on a table or hung on a bulletin board.

If enough signatures are collected in the 60-day period, the petition is filed with the municipal clerk of the city or village. Once filed, the clerk has 15 days to review the petition to determine whether it is sufficient and the legislation is in proper form. When reviewing the petition, the clerk ensures the required number of signatures were gathered within 60 days of filing. The review also includes making sure all required information is provided by the signing electors and is legible, that the signers reside within the municipality in which the petition was filed and there are no duplicate signatures.

Once the review is complete, the clerk prepares a dated certificate stating his or her findings and attaches it to the petition. If the petition is found insufficient, it may be corrected within 10 days of notification to petitioner (contact person named when the petition is filed). Upon certification as to sufficiency, the clerk submits the petition to the governing body (city council or village board). Within 30 days of the date of the clerk’s final certificate, the governing body must act to either pass the legislation without alteration or submit it to the electors as a referendum. If the governing body takes no action within 30 days, it is automatically submitted to referendum.

If the legislation is being submitted to the electors and there are 70 days or more before the next spring or general election, the referendum shall be voted on at the nearest election. If there are less than 70 days before the election, the legislation shall be voted on at the first spring or general election after the 70th day.

When the proposed legislation goes to a vote, only a concise statement of the nature of the proposal will be printed on the ballot. The legislation must be posed as a question, as prepared by the municipal attorney pursuant to Wis. Stats. sec. 10.01(2)(c), and allow the voter to clearly indicate approval or rejection by a straightforward “yes” or “no” vote. If the majority of those voting in the referendum favor the legislation, it takes effect on the date of its publication, which must occur within 10 days after the election.

Direct legislation can be initiated for a variety of subject matters; however, direct legislation authority is subject to the following limitations: may not be administrative in nature; cannot repeal existing legislation (unless it is a charter ordinance); may not exceed the legislative powers conferred upon the governing municipal body; may not modify statutorily prescribed procedures or standards.

Over the last 40 years, a variety of direct legislation initiatives were submitted to the City of La Crosse, one of which was passed by the Council and the others submitted to electors for vote. Here is a partial list:

• April 1988: “Should the City of La Crosse fluoridate its water?” (Approved with 57% voting yes.)

• November 1989: “Shall the City of La Crosse construct a minor league baseball stadium facility and incur any additional costs in connection with the proposed minor league baseball stadium facility on West Copeland Park?” (Defeated with 60% voting no.)

• November 1998: “Shall the City of La Crosse not provide any support for, or incur the City’s share of the estimated $80 million cost of, the construction of the North-South Transportation Corridor along any route proposed or considered by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation

as of November 3, 1998?” (Approved with 61% voting yes.)

• April 2006: “Should the United States begin an immediate withdrawal of its troops from Iraq, starting with the National Guard and Reserves?” (Approved with 53% voting yes.)

• April 2009: a direct legislation petition regarding a City ambulance service. (Adopted by Council; didn’t go to referendum.)

Photo & art credits

Medieval Marginal Art: Anonymous medieval scribes having fun

Photos: Provided by Pam Knudtson except for the public domain image on p. 6.

Cartoon: Tony Auth; The Philadelphia Inquirer Universal Uclick 3.4.2011

Artwork: Illustrations, including the Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy images, were drawn by Roxanne Aubrey as an homage to Douglas Adams.