From the Publisher

Hello, thanks for picking up this zine, the third and final in our Demystifying City Government series. I’m compelled to make both Star Wars and Grateful Dead references: what a long, strange trip it’s been, while Return of the Jedi this is not. But legitimately: how do you wrap something up that doesn’t feel finished? Because that’s what this feels like—a wrap on something undone.

In a way, that was the intent. This series was something of a Pandora’s Box: break the bureaucratic demons out into the light for the average citizen to contend with. That makes it sound much saucier than the reality of your average city government experience, but you catch my drift. It was about clarifying processes and humanizing The City. This is not some abstract place of gridwork roads and boxy buildings that we pass by on the way to our real lives: we all live here, every day, and we have the opportunity, the power, and the responsibility to take care of this place, to make it go, day in and day out. It’s not always saucy, but in the words of our final feature writer, it’s people work.

That’s a quote from Mark Neumann, in reference to democracy on the whole. Neumann is currently a City Council member for the City of La Crosse, and also ran to represent Wisconsin in Congress, twice. Despite his self-classification as an “old white guy,” Neumann’s story of running for office, on the local and/or national level, is not limited to old white men. Certainly not, please,

never again. The ideal is for you, the readers, to see real potential on the campaign trail, to see real potential for yourself, your friends, your coworkers, your neighbors on the campaign trail. Not only on the campaign trail, of course, but in political office, whatever office appeals to you. We need diverse, creative, enthusiastic, and contrasting voices in our local, state, and national governments. So by all means, read and take to heart the heart in Mark’s story, and Run.

And if you do like your Pandora’s Box sauce on the spicier side, take particular note of the sidebar by Jayne Swiggum, aka Nurse Jayne. Swiggum ran for Wisconsin State Senate with an incredibly low budget, and while she didn’t win, she packed a wallop considering her campaign spending vs. the spending of her opponent.

Finally, we have advice from former City Council member Jessica Olson, in her aptly named piece, Welcome to the Fray. Worth noticing is the contrast between Mark’s campaigning ideals and Jessica’s actual experience of sitting on Council. Certainly everyone who gets into government brings their own personal experiences and backgrounds with them, so at the very least, it’s interesting and just a little amusing to read these two voices together, then consider all their potential harmonies and discords. The tension of perspectives is part of the draw of political office—sharpened tools and sharper tongues.

You might even say it’s like snails, with swords.

Maybe you wouldn’t say that. Regardless, our work here is (un)finished. Your turn.

Cheers,

Roxanne and Rachel

by Dr. Mark Neumann, District 13 Council Member

The mechanics for mounting an electoral campaign are simply and thoroughly described in an informational paper by the League of Wisconsin Municipalities.* By following this link, you can learn what you need to get started. Beyond those logistics, what I can offer is my personal story, which gets at the most important question everyone who runs for office will have to continuously confront as they set foot into the political arena: Why do I want to serve my community as a politician? During campaigns, you will have to give hugely of your time (and some resources) while allowing your personal integrity to become vulnerable to criticism in the public space. It’s crucial to know and hold on to why you want to do this.

I have run for office three times, and in each case, someone asked me if I had ever considered running for office; that’s how everything started. Political campaigning is a team sport, and having others help you recognize your candidacy is the first step. I first ran in the 2020 Democratic primary to represent the 3rd congressional district of Wisconsin. Next, I ran in the 2021 spring election to represent the 13th aldermanic district of the City of La Crosse. My most recent bid was in the open 2022 Democratic Primary, once again for the 3rd congressional district, but my actual introduction to electoral campaigning came before my own candidacy, with the 2018 Wisconsin Democratic gubernatorial primary.

Back in 2017, I was already motivated to become more politically engaged. At that time, distressing events had challenged my confidence in our country’s ability to preserve a government of representative democracy; it looked to me like Americans wanted to relitigate issues from our 19th century Civil War. Learning with disbelief about the August 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, it became a choice for me: either sit back, hide, and seek false contentment, or step forward and learn how to become politically active. I chose the red pill to engage, and it worked; when I heard others worry and complain about our evolving national political scene, I experienced a kind of courage and confidence, feeling that I had found something to do about it. I joined a political party, drove to political meetings in the state, met up with other activists at public demonstrations, joined nonpartisan activist groups, and then I met Mike McCabe.

McCabe was the invited speaker at the 2018 La Crosse Progresstival, where he spoke eloquently about state government free of money in politics. When Mike later announced he would run for governor in the Democratic Primary election, I began organizing for his campaign in La Crosse County. My overarching memory of that experience was the fun of it; I felt satisfaction and purpose engaging with the many volunteers as we brainstormed and worked to get the message out about Mike’s campaign. It felt good to march in parades, set up events, meet new friends, and stand in public spaces with signs proclaiming, “Money

Out —People In.” It felt like we were making democracy happen. I learned that political campaigning is People Work: making connections, maintaining contact lists, keeping in touch. It was during this time that I came up with an idea for a slogan, proudly displaying it on a banner, an idea I continue to believe in: “Democracy Equals Neighbors Caring for Neighbors.” Democracy needs a spirit of commitment to the well-being of all members living in a community, a counterweight to the Me-Myself-and-I-ism of greed and selfishness.

Then Mike didn’t win.

Another thing I learned about electoral campaigning is that it hurts to lose. No matter what plain-headed reason tells you about your dismal odds for prevailing, you are in it to win, and you dream for a miracle. In the end, no matter what, it’s still really hard to lose.

Somewhere during that campaign, a friend asked me if I had ever considered running for office. I hadn’t, but I do recall a tinge of jealousy for Mike’s position as the candidate in our race. I was jealous of that leadership role; that’s how the idea first got planted in my head.

After Mike’s electoral campaign, still seeing myself as a political neophyte, I started learning how to engage in policy (or issue) campaigning. In his 2016 campaign for president, Senator Bernie Sanders popularized “Medicare for All.” Prior to that, the 2010 Affordable Care Act had promoted an expansion of the idea that healthcare is for everyone and should be considered a human right; more people began to believe that everyone deserves access to healthcare services. For Sanders, Medicare for All was the best way to make that happen, and during his campaign, it resonated widely.

Even though I had worked in healthcare for 40 years, I had a lot to learn about Medicare for All as public policy. The idea of universal healthcare insurance had been around for decades, but mostly on the fringe of American political conversation. There’s an organization called Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP) that has researched and advocated for single payer healthcare insurance since the 1980s. I joined PNHP and quickly learned what I could on the subject. The inefficiency, ineffectiveness, and injustice of our American for-profit healthcare financing system became overwhelmingly obvious as I delved into the PNHP (and outside) research and data. Following my Medicare for All education, I next learned how to get this information out to the public: people who may have heard of Senator Sanders’s Medicare for All campaign slogan but still needed to learn more about what it really meant.

Policy campaigning is not as exciting as electoral campaigning. Instead of organizing to get a particular candidate’s message out into the political arena, you look for opportunities to meet with people where-ever possible to educate on/discuss a specific subject. I began traveling around, giving presentations on Medicare for All wherever I could. I learned how to do presentations and volunteered to table at public events, including our county fair. I encountered the strong headwind of public opinion bolstered by influencers opposed to permitting significant change from our status quo healthcare financing system. Big profits are being made in the commercialization and commodification of healthcare services and in the selling of private healthcare insurance. Large-scale, privately financed PR campaigns are effective at swaying popular belief that private industry will always do better than public programs like government-run Medicare.

I learned that policy campaigning is a battle of public relations and advertising. Belief in the simplicity, efficiency, and justice of a government-administered payment system like Medicare is undermined by digging up the sludge of political prejudice: that government can’t do anything well, that socialism is bad, that private industry is the only thing that can be trusted. The profiteering industry has a lot of money to invest in its PR campaign for self-preservation, and it does just that to dominate public discussion.

After working on both an electoral campaign and a policy campaign, my next lesson was to learn about the relationship between the two.

In the 2020 summer Democratic Primary election there was only one candidate expected to run for the Wisconsin 3rd congressional district. After months of campaigning Medicare for All policy, I decided to take that policy issue onto the electoral campaign trail by running for office. It seemed a good idea to have two names on the ballot, offering different policy perspectives for people to choose between.

I remember the first time I made a truly public statement about my consideration to enter the campaign. It was at a 2019 gathering of Our Wisconsin Revolution; I had presented on Medicare for All and before the meeting broke up, attendees were invited to express any intentions of running for public office. I raised my hand and was handed the

microphone, and then I had to explain why. In that moment, what came to mind was my late father’s love for our American traditions and his belief in our democratic governance, both of which motivated him to voluntarily fight for and defend in World War II. My simplest answer for running for office was to help that same tradition carry forward. I wanted to hand on to my own son my belief in the democracy that my father handed to me. As naïve as that may be, that is the reason I’ve held on to over my years of work on three electoral campaigns—my effort to help make democracy happen.

There was a huge learning curve for mounting the campaign I was dreaming about. Over time, through study, observation, advice, trial, and error, I homed in on my theoretical approach. My opponent, Congressman Kind, was an accomplished politician who had decades of success running for office. Even so, I had different ideas about what single payer healthcare insurance could represent for all Americans, and I wanted to let everyone know about that during the campaign (in general, my attitude for public policy follows a progressive agenda). But the most important resource a candidate has is their authenticity. I needed to examine my belief system and use what I discovered in order to talk directly from the heart on the campaign trail. It’s the simplest wager of a campaign: if enough voters find my ideas meaningful and they like my character, they’ll vote for me. I had confidence that my character would stand up under scrutiny, so that became my formulation for a campaign: progressive policy ideas and solid personal character.

There are really only two tasks for an electoral campaign: one is to define the message and the other is to consistently advertise that message to enough voters who can believe it and will vote for it. A campaign’s message pertains to both the character of the candidate and what the candidate proposes for good public policy.

Registering a campaign committee and a candidate for federal election is surprisingly easy. The Federal Election Commission (FEC) regulations are easy to learn about, and the FEC staff, in my experience, are quite helpful in answering questions. One of my campaign volunteers and I went to an FEC workshop in Chicago; we spent two days learning about the federal rules and how to keep the accounts necessary for reporting the money-in and money-out pertaining to the business of the campaign. By the end of my first run, I had spent $35,000, about $10,000 of which I personally contributed; the rest came from other individual contributors. We made a few payments for consultants, but otherwise, our workers were all volunteers. For the six months leading up to the August primary election, it was a full-time job. In some ways that was easy; I always knew what I would be doing, sunrise to sunset: working on the campaign. As a private citizen, it’s fair to ask why I would want to put so much personal money into the campaign. It’s because I believed it was an honest and practical way that I could help make our democracy happen, just like I felt while working on Mike’s campaign in 2018.

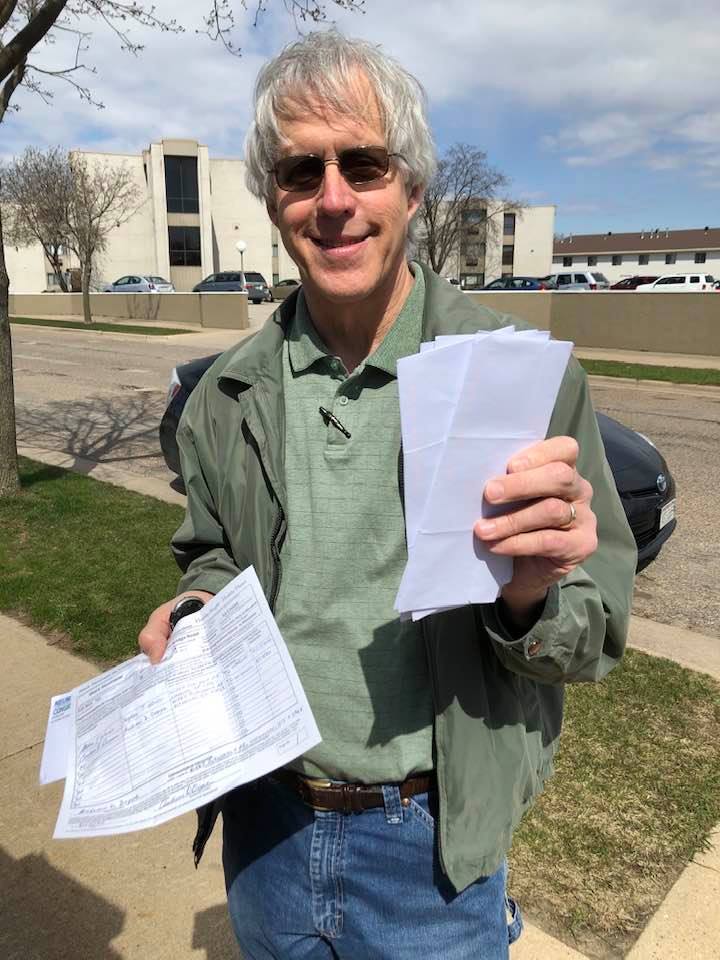

Even before the COVID pandemic began, I was introduced to Zoom, and we were ahead of the curve in using video conferencing to hold our campaign volunteer organizing meetings. To run for this particular federal office, Wisconsin regulations require 1,000 signatures to get your name on the ballot. There’s a window of time—from the middle of April to the end of May—to collect those signatures. Normally, volunteers and/or paid campaign staff canvass door-to-door, and in March of 2020 we were preparing to start gathering signatures when the COVID epidemic was declared. As we entered the big shutdown, our campaign had to switch gears quickly and craft new ways to appeal for nomination signatures. That whole experience is kind of a blur, now, but we relied on the US Postal Service, sending out hundreds of letters with nomination forms and instructions for completing them, one household at a time. By the middle of May, there was a widening gap between the trajectory of forms coming back and what was needed by June 1st. As the initial pandemic shutdown began to relax a bit, I was able to venture out into public spaces with nomination forms, mask, and sanitizer in hand. The walking bridge at Phoenix Park in Eau Claire was a good place to encounter pedestrians and bikers while social distancing. La Crosse’s Riverside Park was another place to meet people and introduce my campaign, person to person. I am especially indebted to a remarkable volunteer who accompanied me in La Crosse; he was a particularly invincible and effective canvasser. By the middle of the last week in May, I could see we were going to surpass our target, and on June 1st, 2020, in the pouring rain in Madison, I jealously guarded a stack of carefully arranged and numbered nomination forms that I confided to the staff at Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC) for counting and eventual acceptance.

Over the course of that April and May, during the start of the COVID pandemic, we worked the campaign as best as we practically could. Our mailers introduced me, my campaign’s progressive message, and my advocacy for Medicare for All. After that, we sought more exposure through county Democratic Party committee Zoom meetings, a Wisconsin Public Radio debate, a WisconsinEye interview, local newspaper articles, social media, and other organizations’ efforts to inform voters about candidates. That summer we weren’t able to hold public events or do door-to-door canvassing, things that under normal circumstances would have been expected. My campaign, along with the many others that ran during that 2020 summer, and all the citizens who found ways to vote as safely as they could, was a testimony to our belief in our democratic tradition. We did it!

Within an hour of the polls closing on election day the results were in: I had lost. A couple days later, I had lunch with Congressman Kind, who went forward in the general election that year to win his 13th term to serve in Congress.

After that, I felt the silence of having lost. Had it all been worth it? It’s extraordinary that in our country, an ordinary citizen like me was able to step forward to run for office with only a dream, resources provided by individual contributors, and the shared effort of a group of citizen volunteers.

Yes, it was worth it.

Sometime later, I heard the election question again, this time from a group of nonpartisan volunteers who were supporting candidates to run for local office. They wondered if I had thought about running for the La Crosse Common Council. I hadn’t, but the more I did, the more I felt that kind of campaign appealed to me. I would be running to represent the people of the 13th District of La Crosse, and when I looked at the map of our neighborhoods, I realized I would be able to canvass all of the district’s streets, visiting door-to-door before the election in the spring of 2021. Meeting person-to-person with so many people during the campaign was something to relish, because it hadn’t been possible during my 2020 campaign. The congressional district had been too vast, and there were no large group, in-person campaign events because of the pandemic.

I contacted my neighbor, the Council Member who had chosen not to run for another term, to ask him what the job was like. His description was straightforward: doing the legislative work of our local city government. I had no particular policy or public issues to motivate my campaign, so my reason for running was again simple: to help make democracy happen. Without a particular policy axe to grind, I would focus on expressing my commitment to do my best to contribute to the legislative work of our local government.

Gathering the nomination signatures was a lot easier for this election. Instead of a thousand, I only had to obtain twenty signatures to get my name on the ballot. I visited households in my immediate neighborhood, door-to-door, and accomplished the task in December.

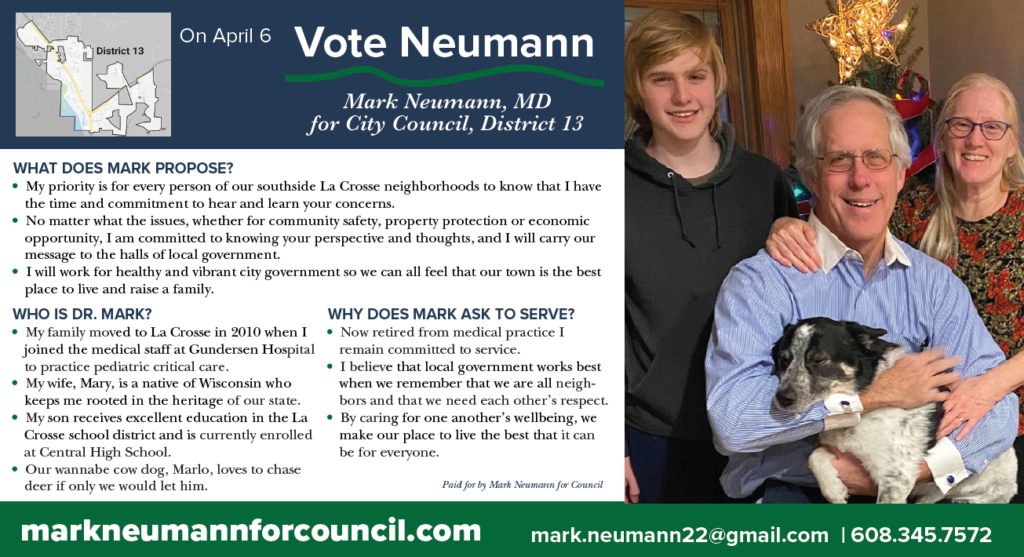

I received an in-kind contribution for the design of a professional quality flyer and mailer. One side of the flyer had a family picture, along with some text to answer the “who,” “what,” and “why” of my campaign, and the other side listed polling place info and a prominent invitation to remember to vote in the spring election. Using my home color printer, I produced door hanger flyers on heavyweight paper that were useful for my personal door-to-door canvassing. I also contracted with a local printer to produce quality mailers that were delivered most economically by “Every Door Direct Mail” via the US Postal Service. Every Door Direct Mail (EDDM)—Targeted Mail Marketing | USPS. The total cost for this campaign was about $1,500, mostly for the mailer. I also contracted with a consultant to create a campaign website, where I expanded on the who, what, and why: Who am I? What policies do I support? and Why am I running? I don’t recall doing much at all with social media, and yard signs were also an expenditure that I avoided. I am grateful for individual monetary contributions to my campaign, but once again I carried most of the financial burden myself because I believed in the value of democratic action.

The best part of this campaign was canvassing for a few hours every afternoon, going door-to-door with a stack of flyers in hand. My goal was to have a conversation at every household; if no one answered, I left a little note scribbled on the flyer. For those who did answer, I engaged in conversation for as long as they desired. We were still social distancing and wearing masks at that point, during the winter of 2021. In spite of that inconvenience, the time spent meeting people in person and listening to their viewpoints was worth it. I believe it’s called retail politics, and it was the best part of what I did for that campaign.

I won the election.

Now I had to learn how to do the job. Our city clerk and city attorney provide newly elected Council Members with an orientation: how to participate in public meetings, how to respect the open meetings rules of Wisconsin, how to communicate with constituents and city staff, how to honor the rules of ethics for public officials, how to become a functional member of local government. The La Crosse Council Member Handbook offers good guidance:

Some things to remember …

• Listen to everyone. Spend time with those individuals who have different opinions than yours. Listen, don’t argue the points, then rethink your position. Remember you represent the entire City. Sometimes you will find it is very difficult to balance the two positions. However, if you keep yourself informed, have an open mind to all viewpoints, listen to your fellow Council Members, the differences of opinion and viewpoints will generally lead to a best solution for the City of La Crosse.

• Develop a thick skin. Remember that people do not dislike you personally, they just (might not) always like your ideas.

• Don’t make promises you can’t deliver. Most major decisions and actions require approval by the (entire) Council. (And you’re only one voice of 13 members.)

• Don’t be afraid to say, “I don’t know.”

• Your job can be very complex. Try to stay focused on the big issues.

• Don’t be afraid to disagree with a fellow Council Member or staff member, but do not make your disagreement a personal attack. Remember, the members of the audience judge the Council by the conduct displayed by each individual. If you embarrass yourself, you embarrass everyone.

There are a lot of wheels turning at City Hall. I’m amazed by the devotion and hard work displayed by city staff and leaders. I thought it would be a good idea to make the rounds, meeting with the city government department heads; mostly I wanted to ask them how I as a Council Member could make their jobs easier. Through those meetings, I learned a lot about the services that benefit all of our citizens, residents, and visitors in La Crosse. One particularly helpful recommendation was to always prepare well for meetings and do my best to understand all the items on the legislative agendas that were up for discussion and vote. This confirmed my own personal expectation that as a representative of the people of my district and of the entire city, I needed to understand what comes before us in the legislative process to the depth that an ordinary citizen of our town would want to understand it. It’s good work.

Some legislative items are fairly simple and functional by nature, but many have long histories, extending over months or even years. These are the product of a great deal of city staff and mayoral efforts and have passed through many board and public committee meetings before arriving at the Common Council. As a current Council member, my primary concern when these items come before us is to know what I’m voting on. I’m grateful for the citizen testimonies at public meetings and for their letters and comments communicated to Council members. The answers to questions provided by city staff and experts are critical. Many times, I’ve tried to ask questions about legislative items at public meetings because I know there are people in the audience and online who might be interested in knowing more about what is happening in city governance and the policies that are being established.

I’m always grateful to hear the questions and opinions of my co-Council members. We all have different experiences and perspectives, so when an issue before the Council is contested, that’s when I’m particularly appreciative of everyone’s votes. We need that shared, accumulated devotion to the work of making good policy for our town. When my vote falls with the majority, I hope that we are correct. When my vote falls with the minority, I am happy to know that there is always more than one path to tomorrow. When we have split votes, it proves we’re all doing our homework, coming up with differing perspectives. The respect I feel for all of my co-Council members makes the job most rewarding.

In the summer of 2021, when Congressman Kind announced he wasn’t going to run for another term, I was contacted by folks who asked if I would run again. I was curious to see how the open primary election would shape up, which new candidates would step forward to run. After a few months, it became evident that no one was planning to include Medicare for All in their campaign message. That’s when I decided to enter the race.

As I’ve stated before, a campaign needs a good candidate and a good policy message that will resonate with voters. This time, I felt some definite weakness as a “good candidate”; there was no getting around the fact that I am “an old white guy.” Even so, I believed my message was distinctive and would run outside the tracks the other candidates were claiming for themselves. I sought the advice of a dozen people who agreed to join a campaign advisory committee and help me out as a sounding board.

In regard to this campaign’s policy message: I believe we are creatures whose greatest strength rests in our ability to cooperate for the common good; for me, this is what progressive public policy represents. I understand that as individuals we each want to make something of ourselves and of our lives as individuals, and we believe we have a right to that opportunity in America. However, there has to be a balance between individualism and collectivism. Too much self-centered greed and selfishness and we destroy the fabric of our society that depends on cooperation and collaboration. Too much imposed cooperative control and we suppress and destroy individual initiative that we all need for the benefit of the society where we live.

In my heart, I hear two voices, and I hear those voices in the speech of others as well: a conservative voice and a progressive voice. Generally, my voice for socialism and collective effort speaks louder than my voice for individual opportunism. For others, I understand it can be different. I still believe it’s possible and necessary to hear and listen to each other, no matter where we fall on the spectrum of conservative and progressive temperaments; this became the theory for my third campaign. Even though I was “another old white guy,” I hoped that a progressive message of social cooperation and collaboration would resonate with enough voters, those who heard that voice loudest in their own hearts. Healthcare financing reform through Medicare for All was the progressive message I wanted to place in the vanguard for the campaign.

Back when working on Mike’s campaign, I learned that in the heat of an electoral effort there are things worse than losing. Believing that the ends justify the means leads people to do things they should never be proud of. The primary task of campaigning is to give voters the necessary information to vote with confidence. Once the objective becomes to win at all and every cost, the guardrails come off, and we actually dissuade people from voting with confidence because deep down, they feel disgusted and disillusioned by the fear tactics and the emotional abuse that gets weighed against them. It was important to me that my campaign didn’t go there. I recalled the words of my son, who once instructed me, “Dad, you know those votes that you want to go after in your campaign are not things, they are people.” With this in mind, I reached out to the other candidates in the Democratic Primary election to ask that we work together to mount respectful campaigns toward each other, culminating in an election we could all feel good about. In that and for that, we all succeeded.

While traveling to participate in candidate forums and other local Democratic Party electoral events, I often crossed paths with the other candidates on the campaign trail; the Democratic Party, through its many local county committees, did a great job organizing events for candidates to participate in. I remember feeling a tinge of sadness while driving home from Stevens Point after our last scheduled event, because that was the last event before the election. I had worked with such a great team of campaign staff and volunteers; I doubt they’ll ever know how much their enthusiasm, effort, and perseverance for the vision of our campaign meant to me. We were all hungry for our progressive hopes to resonate widely with voters, and that camaraderie is powerful.

On election day, the vote count took a bit longer to come in because it was a four-candidate race; even so, it was easy to see early on that I wasn’t going to win. Losing is hard and this reminds me to express gratitude for all candidates who make the effort to run in any election, especially when we don’t win. Without that effort, we wouldn’t have elections, and then how would we make our democracy happen?

After expending so much energy on that campaign, I was tired and concerned that I had been too distracted from my job on the City Council. The task of campaigning and participating in a well-executed Democratic Primary election had become my preoccupation and afterwards, I felt the need to redirect my attention and renew my commitment to the work of the La Crosse Common Council. It’s there that I continue the work of passing on to next generations my belief that we Americans are able to be a self-governing people. I believe in our ability to continuously create and recreate our government of the people, by the people, and for the people.

For those who read this story, I want to assure all that I am immensely grateful for being born in a country that for 250 years has carried on its experiment in representative democracy. I am grateful for the opportunities I have had to make something of myself as a politician. I have had enough experience over the past six years to know it can be a laudable occupation. I want to congratulate all who will make being a politician a part of their life’s work as well. I hope that my story will encourage you to do so.

In 2020, I ran for Wisconsin State Senate District 32 as a Democrat and lost in the primary. Despite the loss, I am quite proud of what I accomplished.

In May 2020, at the very height of COVID, I was outraged when I saw Republican candidate Dan Kapanke at events sans mask, not social distancing, etc. In my fury, I Googled how to run for Wisconsin State Senate and threw my hat into the ring.

I reached out to Jennifer Schilling, who, in an apparent effort to dissuade my running, informed me that I would have to raise at least $300,000 and campaign full time in order to be viable. Initially, I was deflated and considered quitting, but the vulgarity of campaign finance, two-party viability, clear cronyism, and the idea that a working class person has to quit her job to run for a state office fueled my desire to run in a completely different way than any candidate I knew.

I refused to take money from any source and continued working full time as a nurse. I had no no campaign manager or any staff, no advisors, and no help from the Democratic Party—local or state. My family and I made campaign signs from scrap wood, attended various free functions to meet constituents, used Facebook (only the free stuff), and interviewed with local newspapers, radio stations, and television stations at every opportunity.

I knew there was no way I would win, but the outcome was amazing. I spent $261.04 of my own money and received 6,558 votes in the primary. As of 07/27/2020, my opponent, Brad Pfaff, spent $38,878.44 and received 12,631 votes. Each vote cost me 4¢ whereas each vote cost Mr. Pfaff $3.08.

After a second unsuccessful attempt at state office in 2022, I will not run again. The constant worry about getting money to pay for campaign advertising was simply not worth it to me. The lack of support from the Democratic Party of Wisconsin was crippling. Learning through a New York Times article that the Assembly Democrats gave another candidate in a red district $38,000 for a professional campaign manager took my breath away.

The only way we will ever change this system is to take it from the money machine and return it to the people. I believe it is possible, but my experience has left me jaded.

One of your first to-dos as a Council Member (CM) is to go to the City Hall print shop (at the time I was on Council it was in the basement), and request official City Council Member letterhead in 8.5 x 11 inch paper with matching preprinted return address envelopes, and business cards as well. They already have a standard template for CMs which has the City logo, etc. There was no charge to CMs for this when I served. If they want to charge for this, it’s still worth paying for out-of-pocket. Don’t wait until a need arises, it will be too late to have it printed in time. You won’t use it often, but for the occasions that do necessitate it, I’ve found it to be invaluable.

Start Building Relationships & Alliances

Ask the City Clerk for the current hard-copy directory that contains all of the department heads’ contact info. During the first couple of months on Council, many of these department heads will invite you to come for informational sessions and tours of their operations. By all means, attempt to attend and take every opportunity to learn about their department and meet their staff; it signals that you are sincerely interested in understanding the day-to-day operations and challenges first-hand. If you can’t make the official “tour,” or if it’s one of the departments that doesn’t offer new CM orientations, reach out to the department head and ask if there is an alternate time to come in and meet them and learn about their department. The staff talk to one another, and one of the hot topics is always the CMs. Build good relationships early on, before you need to ask for help. If you consistently present yourself as someone who is serving on Council to help them serve the public, you will earn their trust and support.

The staff can MAKE or BREAK your entire experience on Council. There is very little, if anything, that you can accomplish through personal edict or brute force. The staff have ways and means of shutting CMs down if they try to go rogue or steamroll the process. The staff are the ones who actually keep the city running, day in and day out, and they’ve seen their share of misguided, self-serving, pompous, unintelligent people elected to Council. They need to trust you before they stick their necks out to help you.

Due Diligence is not Defamation

I was once told by a former CM that when Council gains a reputation for embarrassing dishonest people during public meetings, it helps to dissuade dishonest people from walking into City Hall to begin with.

At some point you will encounter contentious issues, especially rezonings. Neighbors will provide legitimate or bogus reasons for opposing, and the applicant will give legitimate or bogus explanations as to why some concession cannot be made. It falls on Council Members to sort fact from fiction. If these situations grow heated, you could be threatened for asking questions, and/or your questions could be construed as an assassination of character (three times in four years I had people threaten to file an ethics complaint against me for asking questions or pointing out discrepancies in an applicant’s testimony, but nothing happened). Suggesting that someone is “not remembering/understanding accurately” is the least inflammatory way I’ve found to publicly confront dishonesty.

Here your CM letterhead may be useful. If an applicant states that his financial institution or investors won’t approve financing for the project if he can’t get some waiver or other consideration from the Council, you can use your Council letterhead to communicate with 3rd parties to verify the accuracy of what Council is being told. A voicemail or e-mail can be shrugged off easily, but a physical letter on government letterhead is unlikely to be ignored, and will likely generate a written response. Both letters can then be uploaded to Legistar, the city’s online portal for meetings and documents.

Stand and Deliver

The Standing Committees of the Judiciary & Administrative (J&A) and the Finance & Personnel (F&P) are arguably the most powerful platforms you have as a Council Member, because these committees and their public hearings are video recorded and publicly and easily available online, indefinitely. Even if you are not on one of these committees, you, as a CM, have the privilege to attend and question the speakers to put them on the record. By contrast, the City Plan Commission (which, in some respect, is a “dress rehearsal” for J&A) does not retain video archives for public access, so it is good to attend and listen, but save your questions for J&A, for the record.

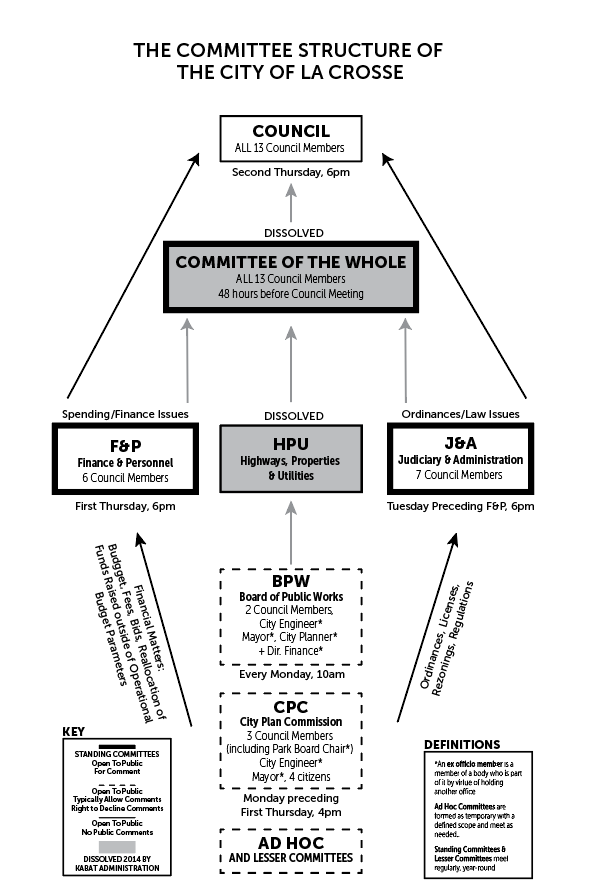

Abolished since 2014, the Committee of the Whole (COW) was a public meeting of the entire Council two days before the regular Council Meeting, a chance to deliberate and cast a “rehearsal” vote. It served multiple important purposes: it gave the public a shot at a public hearing in front of the entire Council, and it gave CMs a second bite at the apple to ask questions of applicants, opponents, and staff, on the record. It also forced CMs to put their vote stance on public display two days before the final vote was taken, so the public knew where each CM stood and could lobby them for an additional 48 hours before the final vote. The elimination of COW reduced the window of opportunity to employ lawyer-like examination to the Standing Committees.

Leverage Legistar as a Clearinghouse

To my knowledge, there is no limit on the number of pages or the number of files that can be uploaded to Legistar. I have never known files to be removed or deleted from an agenda item once added.

For especially complex, large-scale projects, where CMs have staked their support based on questions needing answers or commitments from other governmental units, Legistar is the only way to keep your homework organized and presentable. Legistar 18-0221 is an incredible example of this platform’s power, and Attachment #11 will show you the versatility and power of your CM letterhead to galvanize the myriad elements of a complex project into one mass effort.

BreadCrumb Trails

If the list of questions and concession requests is too long or complex to vet out on video during public hearing, or you anticipate the applicant will be hostile (dodge answering or committing), draft a letter on CM letterhead to bring to the Standing Committee, and use the public hearing to explain that you will present your questions and requests in writing. Bring several extra hard copies of your letter to the meeting, as I usually had multiple media outlets come up to me to ask for a copy. For reference, check out Legistar 18-1255, Attachment #49.

Make sure your constituents who have asked for concessions know that these letters are on public record; they are the “trail of breadcrumbs” to hold an applicant to their promises. I hand-delivered copies of my letter with the Legistar ID # written at the top so in the future, they could search and find the attachments, even if I was no longer on Council. This comes in handy if/when discrepancies arise.

On occasion you will encounter an applicant who is congenial over the phone, makes nebulous verbal promises to appease you, but avoids making written commitments. Asking that person to make their statements in writing is sometimes sufficient in getting them to withdraw a controversial application. One such case was Legistar 20-1706.

Information is the Currency of Politics

Just as wealth takes the form of cash and credit, information can be considered a form of wealth. As people begin to trust you, they’ll share information that will help you make good decisions. And just as currency can be counterfeit, you may encounter false information, and you need to be mindful of the credibility of your sources. One of the more unpleasant necessities of being in local politics is determining the honesty/accuracy of staff, applicants, and sometimes your fellow elected officials. Sometimes it is necessary to ask questions that you already know the answer to in order to discern their credibility. The staff almost invariably tend to be honest and earnest, but you need to know who the outliers are.

In my four years on Council, I had issues with two staff members who would dispense inaccurate information during public meetings. It’s especially uncomfortable when misinformation is made public because then it gets quoted and repeated as fact, since it came directly from a staff member. If you are contending with inaccurate information dispensed live-time during a meeting, you can couch a confronting question by apologizing for being new and not understanding things (even if you’ve been on Council for a couple of years). State your understanding on the matter and ask the staff member to go back and verify which one of you is remembering correctly before further discussion or voting.

Political Firebugs

The documentary film Land Grab is a tear-jerker for any CM who has watched a good project go down in flames because of “political firebugs”: people who purposely spread false information, on social media and beyond, in order to defeat a project at any cost. Get to know the local journalists on City beat early in your Council career, exchange business cards, and engage in small talk.

Always return their calls, and instead of declining to be interviewed, refer them to another staff member who can better answer their questions. Someday you will have to put out a PR dumpster fire to protect innocent people and the media is your best shot at fighting misinformation.

Info-Mining & Easter Eggs

To continue the “information is currency” analogy, information can also be mined when you look in the right places. CCAP will give you information about court cases, arrests, bankruptcies, lawsuits, tax warrants, and more. Police reports can be open record requested. The search page for La Crosse County Property Records will give you details about property ownership, structure type, tax records, sales history, and assessed values. Meeting minutes for both City and County are all online. The internet, with an appropriately worded search, can pull up documents that were presumed sealed and inaccessible. Various websites can give you all the LLCs affiliated with a person’s name in a given state (you may want to then search those other LLC names on CCAP). Reverse image searches, social media searches, and googling emails, addresses, and phone numbers will sometimes reveal some shady side business that a developer didn’t disclose or other things that warrant inquiry before the City engages in a development agreement.

The La Crosse Public Library maintains a superb online archive of the La Crosse Tribune. You will only be able to access identifying info and an abstract, but this is enough to find the full article on microfilm. Grant Blum and Joan Kent left a lot of Easter Eggs in those articles (quotes from past elected officials; applicants making promises or explaining intentions). I once used a Tribune article that was 25 years old to derail a misguided piece of legislation.

Other informational “Easter Eggs” may arise in the form of conditions that were placed on agreements under past staff members. Most often you’ll see these when someone asks for a restrictive covenant to be removed or an agreement amended. Presumably, there was good reason for such conditions to be put in place, so research carefully and don’t undo hard-won gains.

Finding Spare Change in the Couch Cushions

As soon as the Capital Improvement Project (CIP) Budget is released to the City Plan Commission (CPC), request a printed coil-bound copy from Finance. They used to automatically provide each CM with hard copies but stopped in 2021. You will struggle to follow all the amendments as they go during several special meetings of the CPC (forget about trying to construct an amendment without one!). This document is so critical it would be worth paying out of pocket for.

In order to stay ahead of the curve, you can also obtain a map of the Tax Increment District (TID), including its ½-mile boundary. Along with the map, you can request a written explanation from Planning on what they consider eligible/ineligible Tax Increment Finance (TIF) expenditures. This should include information on how much money is available in each TID that hasn’t already been allocated into the budget.

If you are going to attempt to amend the budget, be aware that there are multiple layers and sequences of approvals to acquire, and you are at risk of getting caught in the moving gears of other staff and elected officials who are also attempting to make their amendments (you can imagine the chaos if multiple people try to poach money from the same line item in the same meeting). The safest way to avoid the “moving gears” problem, if you can afford to block off several days in a row between the F&P and day before Council, is to wait until the dust settles at F&P. Hop on Legistar and download and print all the previous amendments and update your hard copy of the Budget Book. Now that you have an accurate picture of where all the buckets of money currently sit and what kind of funds they are, you can start the process of turning over couch cushions to look for money that can be moved around.

The topic of government money: where it comes from, how it can be spent, where geographically it can be spent, how soon it needs to be spent, and what it can be spent on is a topic that deserves its own volume, but here is a slightly irreverent nickel-version explanation:

General Obligation Bonds (GOB) are the most flexible source, with hardly any restrictions other than that it cannot be used for an operating expenses. Ideally, you would be looking for other “buckets” to pilfer from in order to free up GOB money allocated to other projects so that it is reallocated to the project you want to prioritize.

Tax Increment Finance (TIF) funds are also pretty flexible but are restricted to use within a ½ mile radius of the Tax Increment District (TID). My technique was to find something TIF-eligible currently taking up GOB, shifting the funding source to TIF, then shifting the GOB funds to the project I wanted to support.

State Trust Fund has money available for property acquisition, albeit at a higher interest rate than bonding, but it is a source of funds that can be raided if you need to push a line item around to free up GOB or TID money.

Residual bond funds from recently completed projects: keep in mind that most City projects have a 10% buffer added as a line item, labeled “contingency,” to cover minor overruns without having to come back to Council. Many projects do not use up the full 10%, or even finish out under budget. These funds do have some restrictions related to the bond that was originally issued, but it never hurts to ask Finance how much is available and what the permitted expenditure categories would be.

Enterprise funds are generally locked up and restricted to use by that department, so forget about pillaging the Airport, Sewer, or Water Utility line items to fund a new park shelter.

Streets are mostly fair game, and I’ve done my own drive-by in person to see if a rarely used side road section could be pushed off and convinced Engineering to support delaying a year; this can potentially be hundreds of thousands. Sometimes there are legitimate reasons for ripping up a road that still has useful life, so don’t get excited until you hear back from Engineering—sometimes a larger scale utility project is being done in conjunction with a street repair that they are doing early for the sake of cost savings. If it can’t be pushed off a year, are there any TIF funds that can be used to free up GOB funds?

Final Thoughts

THANK YOU for taking on the responsibility of serving on City Council. I hope your experience will be overall a positive one, as well as an opportunity for personal growth and friendship and camaraderie with your fellow Council Members. Our city’s future relies on you. There may be some who would disagree or even be offended by what I’ve written, and much of it will be cryptic until you start to encounter situations in real life. I hope that what I have offered here will help you navigate your journey and lead La Crosse to a better future. Godspeed and goodnight.

La Crosse City Clerk: Candidate for Elected Office

Wisconsin Elections Commission

UW Extension – Local Government Center

Wisconsin League of Women Voters

Wisconsin Counties Association

League of Wisconsin Municipalities

Nation Builder: “How to run for office” free webinar

Leader Ethics: Becoming a Candidate on an Ethical Leadership Platform

Photo & art credits

Medieval Marginal Art: Anonymous medieval scribes having fun

Photos: Provided by Mark Neumann